Slow looking: taking my time watching a Moorhen and a Little Egret

- Sim Elliott

- Dec 4, 2020

- 4 min read

Slow looking is a form of mindfulness and, as such, an antidote to mindlessness and distraction. It teaches us to be present in our lives. In environmental terms, it’s a way of valuing what is local (the art immediately before us) over the global (everything that takes us elsewhere). David M. Lubin, “Slow Looking” (2016)

On Monday I went to Widewater Lagoon, Lancing and Broadlands Park, Worthing, on a particularly cold and dark day.

At Broadlands I followed a swimming Moorhen for 30 minutes. Moorhens are one of the world's most common birds, but commonness does not mean moorhens are not beautiful or interesting. The Collins Bird Guide (2nd ed.) notes that the Moorhen is quiet a secretive bird. The one I watched seemed particularly skittish when I tried to photograph her. I particular wanted to get a sight of her feet and toes, as Moorhen's toes are extraordinary; they enable Moorhens to walk on mud and floating vegetation, as if they are walking on water. She hid from me, going under different parts of the overgrown vegetation of the lake bank, into more and more inscrutable locations. I pondered whether she knew I wanted to photograph her and was being awkward to annoy me; but this was sheer anthropomorphism. Her hiding was much more likely to be an innate protection from predation (by foxes, raptors, or humans) behaviour; I wondered if there was an innate response to seeing something that looks like a gun, like a long-lensed camera: "evolution has acted so that genes and environment act to complement each other in yielding behavioral solutions to the survival challenges faced by animals." Breed, M. & Sanchez, L. (2010). Moorhens, along with other water fowl have ben hunted for hundreds of years. The UK Game Act of 1831 allows coots and moorhens to be shot between 1st September and 31st January; and in the US Moorhen hunting is still a popular "sport"

The Moorhen eventually became invisibly; somewhere under the overhanging foliage at the edge of the lake. I kept on looking at the place I thought she was hiding, and after some time (after some children feeding close-by Mallards had gone) she reappeared. tentatively; giving me a great view of her feet and toes. Moorhens' plumage, that looks just black when far off, is beautiful and variegated when seen close-to; a combination of brown, black, and mauve, set off with creamy-white along the flanks; with a stunning bill: red at the base and yellow at the tip. Patience is a virtue. My photographs of this Moorhen aren't that great, but they are a record of the pleasure of eventually seeing her beauty.

Before the Moorhen hid, I took various photos of her swimming.

I am intrigued by the relationship between art and photography. Undoubtedly, photography has greatly influenced painting and printing since the invention of photography in the nineteenth century, however, art is an influence, perhaps unconsciously, on how photographers, even amateur photographers like me, compose shots. In my childhood my parents greatly enjoyed Japanese prints and I saw them in art books frequently. A feature of Japanese wildlife woodblock prints is the way in which the birds are placed; not in the dead centre of the image, and often with "empty space" around them.

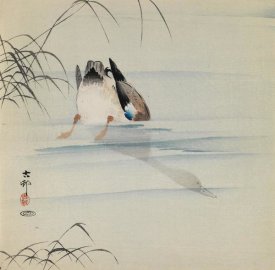

The following are works by Ohara Koson (小原 古邨, 1877 – 1945), a Japanese painter and woodblock print, part of the shin-hanga ("new prints") movement and a master of kachō-e (bird-and-flower) designs.

I wonder if visual memory of these Japanese images influences me when I press the shutter button. Although one should not underemphasise the role of luck in photography. Animals often move quickly; in the time it takes to press the shutter button and the camera to take the image, animals have often moved from where you saw them in the viewfinder.

On the way back home from Broadlands, I stopped off at the Widewater Lagoon; as usual there was a Little Egret foraging for food. I spent a long time watching the Egret's foraging technique: lots of leg shaking to stir up small fish and crustaceans. Little Egrets' behaviour is fascinating to watch. I watched and watched waiting to this Egret catch something; but he didn't. His patience was admirable .

The more I look at Little Egrets the more I am taken with their beauty, especially the long feathers which seem to tumble from their head, "stooped shoulders" and their breast.

The beauty of their plumage was noted by Thomas Bewick, in his pioneering "field guide", History of British Birds (1797-1804). Bewick made the wood engravings and described each bird with text.

The Egret is one of the smallest, as well as most elegant of the Heron tribe: its shape is delicate, and the plumage white as snow; but what constitutes its principal beauty, are the soft, silky, flowing plumes on the head, breast, and shoulders; they consist of single slender shafts, thinly set with pairs of fine soft threads, which float on the slightest breath of air .

Today a Little Egrets' beauty can be easily seen, as they can frequently be observed locally (e.g. Widewater Lagoon, Lancing; Adur Estuary, Shoreham; Cuckmere Haven) but for Bewick the beauty of a Little Egret must have been a rare pleasure:

The species is found in almost every temperate and warm climate, and must formerly have been plentiful in Great Britain, if it be the same bird as that mentioned by Leland, in the list or bill of fare prepared for the famous feast of Archbishop Nevill, in which one thousand of these birds were served up. No wonder the species has become nearly extinct in the is county! (Vol II. Containing the History and Description of Water Birds pp. 45-46)

Slow looking is a pleasure.

Comments